Asset allocation should be guided by investor characteristics

When it comes to building portfolios and designing asset allocation policies, it is crucial to consider investor characteristics. Different investors have different objectives, constraints and risk tolerance. Pension funds must cover liabilities streams, endowments and charities need to cover regular spending needs, sovereign funds often aim to preserve capital in perpetuity.

The context faced by every investor is unique. In practice, however, the extent to which investor-specific objectives, constraints, and risk tolerance guide asset allocations varies considerably. These aspects of asset allocation decisions can often be neglected, compared to expected return and portfolio risk considerations.

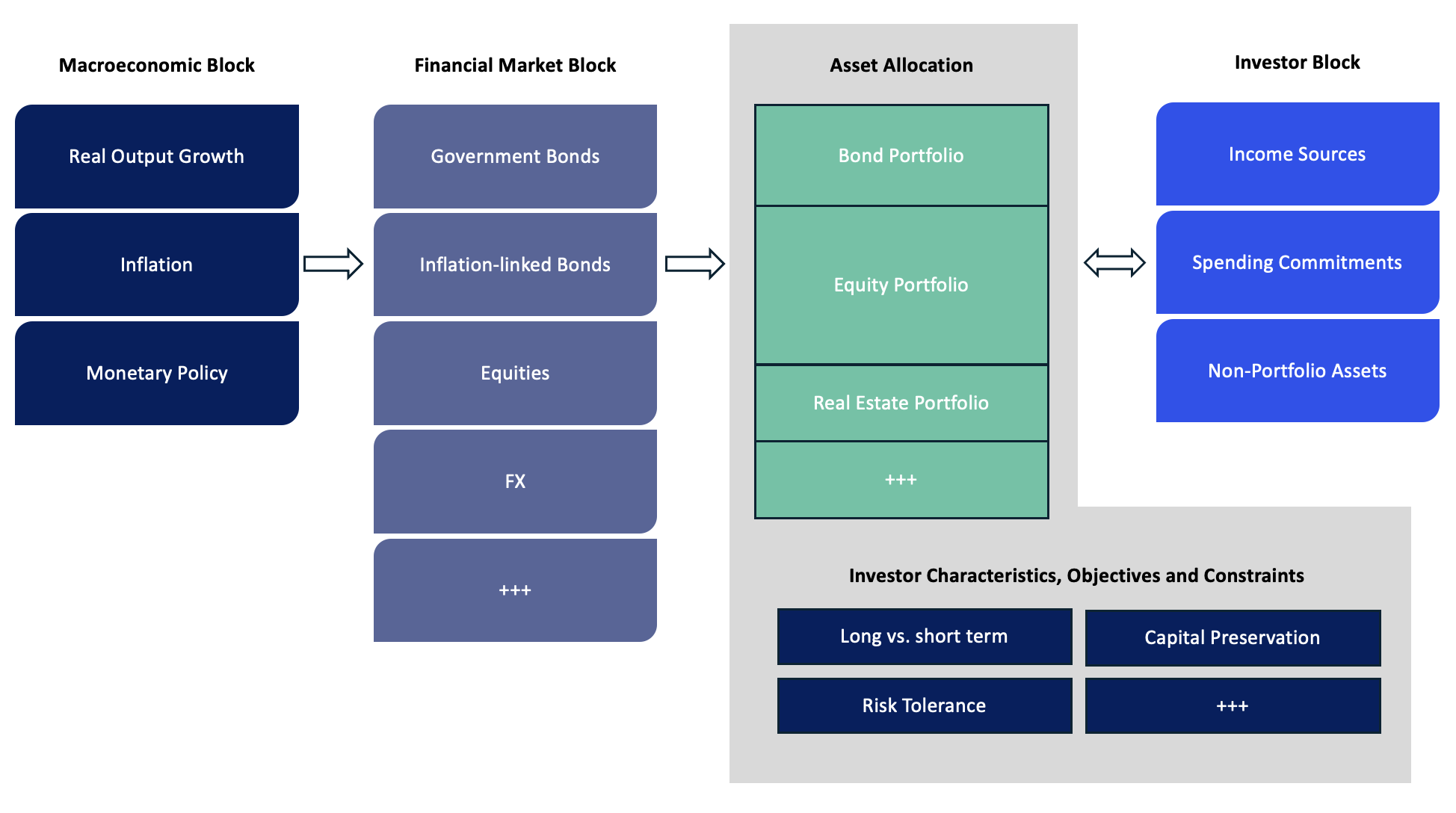

Our asset allocation approach emphasizes modelling of investors themselves. We rely on a forward-looking approach to help investors understand returns and risks in their individual circumstances. We use simulations of alternative portfolios to help investors understand their asset allocation decisions. An important step is to build a component in our simulations that represents the investor -- as highlighted in grey in Figure 1. In this sense, we can quantify investor characteristics.

Figure 1: Representing an investor’s asset allocation problem, an illustration

Data and modelling of investors

All asset allocation solutions need models of asset returns when constructing portfolios. We always model asset returns, though we think certain extra steps are required for modelling return drivers, especially over the long term. This is an incomplete setup for an investor, however. Modelling asset allocation also means modelling the investors themselves with all their unique characteristics, not just the markets and asset returns.

For example, a sovereign fund that finances part of the government budget can be directly modelled through understanding the behaviour of fiscal revenues, spending, and deficits. These variables can then be understood alongside simulations of asset returns over different horizons. Simply by taking this step, we can better understand which aspects of asset returns and characteristics are of first-order importance for investors.

Focusing on key intuitions and experimentation

Many asset allocation approaches involve some kind of optimization. This is often useful for uncovering intuitions that should underlie asset allocation decisions. In practice, however, solving for an optimal policy often produces a ‘black box’: a solution that is difficult to fully understand especially in complex environments.[1] This outcome also tends to be associated with instability in optimized parameters: a small change to inputs such as expected returns can produce radically different optimal portfolios.

We view simulation-based approaches - based on a robust return-generating engine - as a way to mitigate these issues. Essentially, we want to set up as realistic a ‘laboratory’ as possible for investors. With realistic simulations of asset returns over an investment horizon, combined with an effective representation of the most important variables faced by an investor, we can experiment with different approaches.

Explore all asset allocation parameters

Different variations of the simulations can be run as many times as needed to understand the implications of different choices of weights for asset classes, rebalancing policies, or spending behaviour. Investors can stress test their decisions to changes in how markets operate, to different return correlations, and to changes in how their liabilities fluctuate in different market or economic conditions. This is naturally a highly bespoke exercise.

The simulations allow for essentially unlimited explorations. For example, investors can construct a risk measure of their choice, choosing to focus on outcomes in the distribution of their portfolio returns that are least preferred, over any horizon. In addition, we can think of risk both in a portfolio return sense, but also in the sense that an endowment, sovereign or pension fund may not be able to cover their spending commitments or liabilities.

An important feature of the model is the ability to connect macro variables with portfolio outcomes. This helps us ensure that risk management and scenario exercises remain intuitive. For example, we are able to explore portfolio performance under a scenario where long-term GDP growth potential slows over a long period of time.

Case study: the Norwegian Sovereign Wealth fund

A demonstration of our approach can be seen from our time spent working for the Norwegian sovereign wealth fund. The fund is integrated into the Norwegian economy, where each year part of the government budget deficit is financed from the fund. In addition to this spending commitment, the fund also aims to preserve capital over the long-run. We spent considerable time building an understanding of the nature of government spending and revenues, in order to represent these variables stochastically. This allowed us to model the fiscal deficit alongside financial markets and expected returns.

This modelling effort generated a realistic environment for understanding different rules for withdrawing from the fund. We could ask how deficits would behave if spending strictly in line with expected returns – the only ‘sustainable’ option for preserving capital over the long run. On the flipside, how adverse would spending counter-cyclically be for capital preservation aims? The possibilities are vast – with a better understanding of these trade-offs one could explore how to design asset allocation policies to combine with spending policies.

Interested in finding out more? Use our contact form to continue the discussion.