The discounted cash flow logic

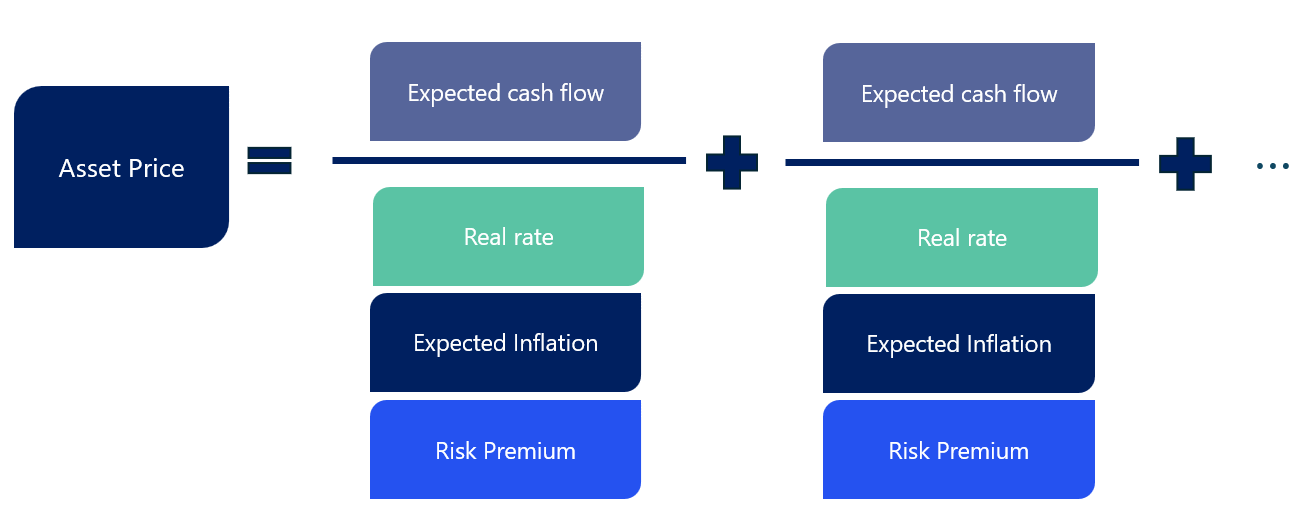

Asset prices reflect the present value of future cash flows,[1] which can take many forms including dividends, coupons, rental payments or royalties. The rate at which these cash flows are discounted consists of the risk-free rate and the risk premium, where the risk-free rate can be decomposed further, as shown in the chart below:

Figure 1: Cash flow and discount rate components, an illustration

While the expected cash flows on individual assets reflect their idiosyncratic prospects, once aggregated to the asset class level, they become closely linked to the macroeconomic outlook as asset-specific factors tend to average out. Asset class returns are generated by a combination of revisions to investors’ cash flow expectations and changes in components of discount rates. Collectively, we refer to these revisions and changes as macro drivers of asset returns.

The risk-free part of discount rates is common to all assets, and the risk premium is asset-class specific.[2] Levels of the risk-free rate across maturities reflect investors’ expectations about the path of central bank’s policy rate and are thus closely linked to monetary policy. When setting policy rates, central banks consider not only the inflation outlook but a full range of macroeconomic factors, perhaps most prominently the growth outlook. Consequently, broad asset classes such as equities, government and corporate bonds or real estate are linked to macroeconomic variables such as output growth, inflation or monetary policy.

Although the conceptual link between asset prices and macroeconomic variables is clear, establishing empirical links between macro variables and asset returns is a non-trivial undertaking. There are at least two reasons for this:

- Asset prices reflect expectations about macro variables across horizons, stretching far into the future. Eliciting and modelling investors’ expectations across horizons is challenging – and the challenge grows at longer horizons. As we elaborate on below, this is the area where our offering is differentiated from other approaches.

- A changing macroeconomic outlook simultaneously impacts cash flow expectations and components of discount rates. As a result, the moves in expected cash flows and in the components of discount rates can fully or partially offset each other. However, this does not mean that changes to macroeconomic outlook do not matter for asset prices or that asset prices are disconnected from macro.

In our asset allocation approach, we address the first challenge by explicitly modelling expectations and risk premiums for each horizon, which gives rise to term structures of expectations and risk premiums. To do this, we combine a wide range of forward-looking data such as derivative prices and professional surveys. When using this data, we pay particular attention to how investors form expectations about the short- and long-run. These features are unique to our framework.

A good example of the offsetting impact of a changing macroeconomic outlook on expected cash flows and discount rates is a revision of the growth outlook in either direction: an improving growth outlook lifts equity investors’ assessments of expected dividend growth, which is positive for equity prices, but at the same time it might lead to an upward revision of the real rate which is a negative shock for all assets.

To complicate things further, risk premiums associated with expected dividend payments are likely to react too. The discount rate itself has a number of moving parts that can partially offset each other. A worsening growth outlook is usually accompanied by an increase in the risk premium investors require to hold risk assets such as equities. At the same time, central banks tend to lower their policy rates or communicate their willingness to do so, which lowers discount rates through lower real rates. Similarly, there can be interactions between expected inflation and the real rate.

Careful and granular decompositions of returns on a wide range of asset classes help us trace out the key channels through which macroeconomic variables impact asset prices. Once we account for all channels, asset class returns are indeed tightly linked to a changing macroeconomic outlook.

From asset classes to macro drivers

Various asset classes share common macro drivers. Starting with the discount rate: all asset classes, irrespective of their cash flow profile, are exposed to the risk-free component (equilibrium real rate, monetary policy and inflation expectations), which underlines the importance of these macro drivers. Real estate, for example, illustrates this on the cash flow side, as it shares both equity and fixed income risks. Hence, real estate returns are driven by equity risk and term premium variation. From this perspective, asset class returns are different bundles of exposures to macro drivers.

Mapping returns on a wide range of asset classes to distinct and intuitive macro drivers brings asset allocation to a new level by improving the understanding of risks and opportunities associated with each asset class. Looking at the portfolio from this perspective, it is easier for investors to see the incremental macro risk that a new asset class adds to their portfolio and what the performance would be under different macro scenarios.

Interested in finding out more? Use our contact form to continue the discussion.