Expectations link asset returns to macro

Modelling expectations about macro and policy variables such as real GDP growth, inflation or central bank rates is a key step in pricing financial assets. A complicating factor in modelling expectations about the evolution of these variables is that they all have complex dynamics and are persistent. Why is that the case? It is because they themselves are a result of myriad effects. A good example is the policy interest rate: when setting interest rates, central banks consider a wide range of indicators, all of which contribute to the resulting dynamics. At the same time, central banks tend to adjust monetary policy gradually in order to avoid abrupt moves, which contributes to the high degree of persistence in interest rates.

Long-horizon expectations and macro trends

Investors and market commentators tend to focus on short-term expectations: the path of GDP growth or inflation over the next couple of quarters, or central bank actions over the next few meetings. Short-term expectations are undeniably important, but this especially true to the extent that they inform long-term expectations. Discounted cash flow logic tells us that long-horizon expectations, e.g., 5+ years out, are even more important for the pricing and the risk assessment of long-duration assets such as equities, real estate and long-term bonds.[1] A changing market consensus about the growth prospects ten years out impacts not only the cash flow expectations at the ten-year horizon but also all shorter-term expectations. Moving from the asset class to company level, only slight changes in expectations of terminal growth or discount rates are required to produce wildly different market values in a discounted cash flow model.

Long-horizon expectations about output growth and inflation, and their revisions, are important drivers of asset class returns. We collectively call them 'macro trends' – a label that reflects their slow-moving trend-like behaviour. Long-horizon growth expectations are closely linked to the long-term level of real interest rates – often referred to as the “equilibrium real rate” or “r-star”. To the extent that r-star anchors the risk-free component of discount rates, it is a key variable for pricing all assets irrespective of their risk profile.

From the perspective of investors, it is important to produce real time estimates of macro trends, which can differ substantially from what can be identified in historical data using statistical methods. As a result, there is a wedge between what investors can estimate real time and what can be uncovered using statistical methods ex-post. Understanding and considering this wedge in the investment process is extremely important, especially for tactical asset allocation strategies that aim to exploit the wedge.

The most common way of representing expectations is to estimate statistical models using historical data. One prominent model in this category is the Vector Autoregression (VAR), which represents current and expected future values of variables as a function of their past values (lags). There are several issues that complicate the use of VARs, especially at longer horizons.

First, VAR model parameters are often estimated using the full history of data, and do not therefore generate real-time expectations. Second, an implicit assumption in this type of model is that the structure of the economy and the policy environment are stable over time. In fact, in some versions of VAR models, long-term expectations are essentially constant. Clearly, this assumption is violated in reality – economies and policy environments undergo lasting shifts. Attempts to amend the VAR-based approaches to accommodate regime changes are not without problems either – not least because they tend to rely on very complex modelling.

Finally, a high degree of persistence in macroeconomic and financial variables leads to imprecise estimates of endpoints for these variables. A relatively small degree of imprecision leads to relatively large expectational errors at longer horizons – contributing to the wedge mentioned above. To accurately represent long-horizon expectations in real time, we need an approach that works well in the presence of regime changes and can deal with persistence.

Real-time estimation of macro trends

An alternative to long-horizon expectations from VAR-based models is to use professional surveys where possible. Surveys, such as Consensus Economics, Survey of Professional Forecasters, Blue Chip or I/B/E/S regularly collect individual forecasts of key macroeconomic and financial variables made by professional forecasters. The median survey-based forecast has been shown to perform at least as well as other types of forecasts (model- or market-based), and in some cases outperforming them. Importantly, the surveys are available in near real time.

As an example, using a VAR model with constant long-horizon expectations during the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) would have led investors to conclude that yields on government bonds will rise to the pre-GFC levels once the acute phase of the crisis was over. Using forward-looking data such as professional surveys and signals from asset prices would have helped investors avoid misreading the ensuing macro environment. Unsurprisingly, professional surveys are gaining prominence among investors as a way of approximating market consensus on key macro-financial variables. Professional surveys collect forecasts across horizons, including long horizons (10 to 30 years ahead).

Adaptive expectations

In cases where professional surveys are not available or in simulation applications, using an adaptive expectations model is a good alternative for modelling long-horizon expectations. Adaptive expectations rely on the idea that investors use incoming realisations of macro data to partially update their long-horizon expectations. The degree of updating is specific to each macro variable and depends on its properties. Forming adaptive expectations turns out to work well in the presence of regime changes and other forms of instability. To deal with instability, adaptive expectations assign higher weights to more recent observations of the variable and place lower weights on observations in the more distant past.

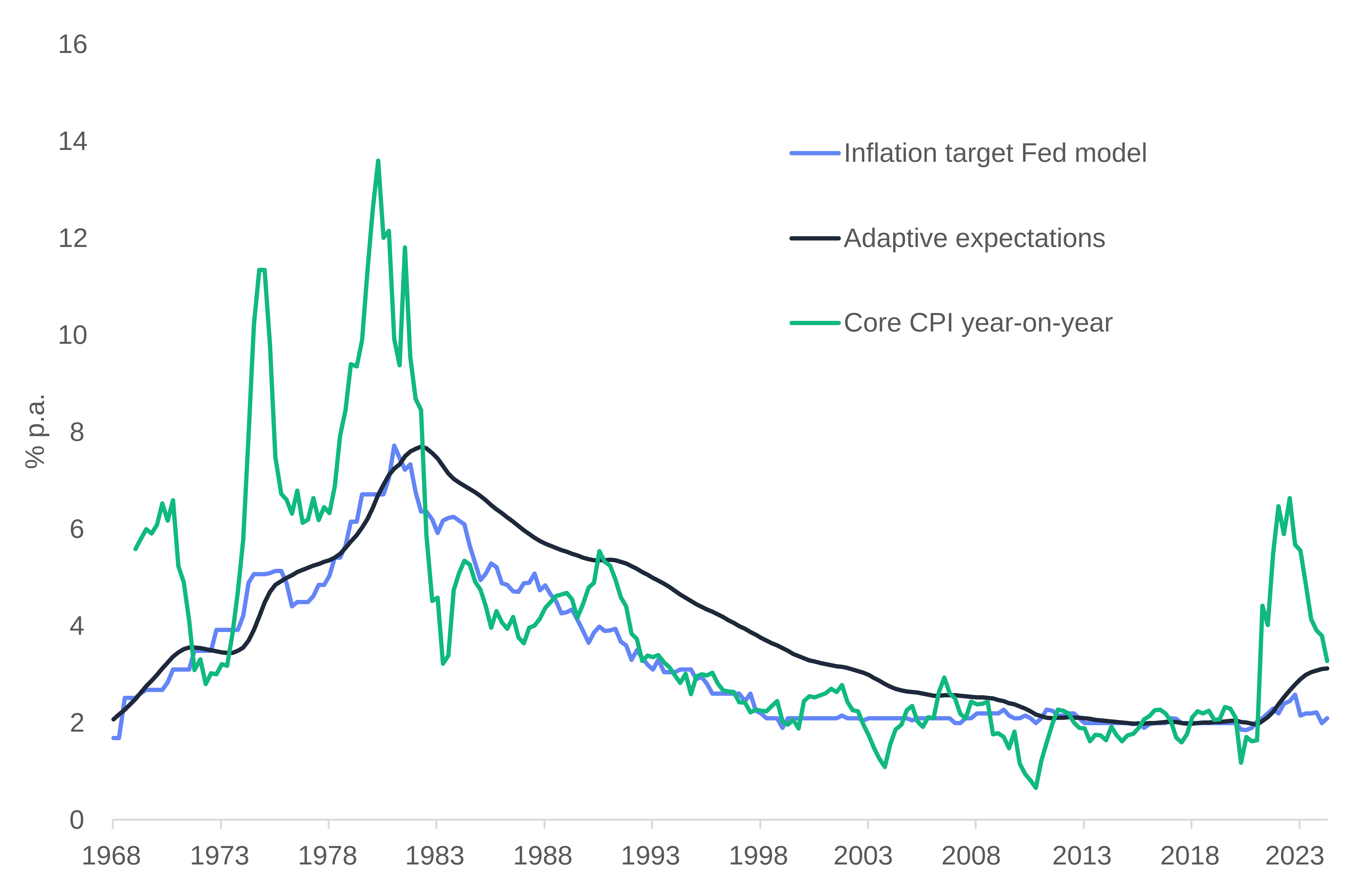

Figure 1 below compares the long-horizon expectations relying on professional surveys (light blue line “Inflation target Fed model”), which refers to long-horizon inflation expectations used in the Federal Reserve Board's FRB/US model, and from an adaptive expectations model (dark blue line).

Figure 1: Modelling long-horizon expectations for inflation

The chart shows realised core CPI inflation in the US and two measures of long-horizon inflation expectations. The dark blue line represents adaptive expectations obtained as a discounted moving average of past core CPI inflation. The light blue line represents the inflation target from the Fed model.

Both versions of long-horizon inflation expectations track each other relatively closely and, importantly, reach their peaks simultaneously. Compared to short-horizon expectations, which track realised inflation much more closely, long-horizon expectations tend to move slowly over time, creating a trend-like behaviour. As noted earlier, an estimate of long-horizon expectations from a regular VAR model would be a constant while our estimate of long-horizon expectations drifts between 2 and 8 percent.

For more on long-horizon inflation expectations and how they relate to yields on government bonds, see Cieslak and Povala (2015). This publication has nudged researchers to improve the modelling of long-horizon expectations and highlighted the importance of doing so for asset pricing.

Our implementation

Within our ASAMM suite of models, we realistically represent the investors’ expectations and their evolution over time and across horizons. To do this, we embed forecasts from professional surveys in our present-value models and return decompositions which helps us to accurately represent the term structures of investors’ expectations about key macroeconomic variables. In simulation-based models, we represent investors’ long-horizon expectations through adaptive learning. The implementation of these models draws on our extensive experience in researching and implementing asset pricing and allocation models.

Perhaps the most important benefit of carefully modelling long-term expectations is a more accurate representation of expected returns and long-term risk attached to different asset allocation choices. In particular, neglecting the modelling of investors expectations, especially at long horizons, can lead to an underestimation of long-term portfolio risk.

Interested in finding out more? Use our contact form to continue the discussion.

References

- Chin, M., and Povala, P. (2024). Simulating Long-Horizon Returns on Government Bonds. The Journal of Fixed Income. Vol. 34, No. 2

- Cieslak, A., and Povala, P. (2015). Expected Returns in Treasury Bonds. The Review of Financial Studies. Vol. 28, No. 10